Now that my official Imaginaerum OST gig is close to its final stages (the 7.1 stems are already in Canada as I write this), I’m taking some time to open up a few techniques used in the sound design and pre-production stage, concerning both the creative method and the application/plug-in side as well. I wrote a rather sketchy blog article focusing on the project as a whole for Nightwish’s Imaginaerum The Movie facebook page (on.fb.me/H2onWf). Me being such a geek – well, a 30% geek, because the other 70% wants to rock with my cock and other pets out – wanted to elaborate the technical side a bit. I’d say the experience level for reading this is somewhere between beginner and intermediate. There’s nothing new or groundbreaking in what I’ve done, that must be said right here, in the beginning.

Now that my official Imaginaerum OST gig is close to its final stages (the 7.1 stems are already in Canada as I write this), I’m taking some time to open up a few techniques used in the sound design and pre-production stage, concerning both the creative method and the application/plug-in side as well. I wrote a rather sketchy blog article focusing on the project as a whole for Nightwish’s Imaginaerum The Movie facebook page (on.fb.me/H2onWf). Me being such a geek – well, a 30% geek, because the other 70% wants to rock with my cock and other pets out – wanted to elaborate the technical side a bit. I’d say the experience level for reading this is somewhere between beginner and intermediate. There’s nothing new or groundbreaking in what I’ve done, that must be said right here, in the beginning.

Plunging into the world of a finished track by means of some Protools project file and everything it consists of, is a really long day’s work. Usually it took two to three days to just prepare the raw material for further processing, do the rough edits, truncate begins and ends, etc. Luckily Nightwish’s mixing engineer, Mikko Karmila, is a hard-boiled pro, who names everything carefully and keeps everything really tidy. The project files were perfect. There were even short notes about microphones used, made by himself or any assistant engineer. It was a peek into a magical world, as I’ve admired Karmila’s productions as long as I can remember, and he’s also one of the very few persons I truly appreciate.

At the listening/selecting stage I virtually had no idea whatsoever what the tracks would turn into. I just listened track after track after track, starting from Jukka’s drums, his overhead stereo file, room mics… everything, and proceeded further track by track. If there was a nice note or a rhythmic thing that caught my ear, I’d cut it off and immediately check the neighbour channels if they happened to share something with what I had just cut out. Sometimes there was suitable audio material, sometimes not. I tried to find patterns, both rhythmical and harmonic. For instance, Marco’s bass playing usually accompanied Emppu’s guitar shredding, so it was natural to chop out similar one bar, two bar, four bar performances from the neighbours as well, whatever there was.

With Jukka’s rhythmical stuff, I bounced some stems from his separate kick-snare-hat-toms-cymbals(overhead)-room-whatnot tracks and transferred the stems into Ableton Live. To those non-musicians, Ableton Live is a clever piece of software that allows separate handling of time and pitch, unrelated to each other. Usually, if you’re lowering the playback speed, the pitch of the signal will lower, too. Just like on the cassette or a vinyl. (If you’ve been around long enough to use such machinery.) That speed/pitch treatment could be done on pretty much every other tool or DAW as well, Protools among them, but Ableton Live’s got many nice built-in tools and plug-ins for mangling the audio stuff beyond recognition. My favorites for Live drum/percussion treatment are Corpus and Resonators. I also did some MaxForLive programming for weird higher-end audio treats. Stuff that mangles stuff, you know.

A good mixture of Resonators and Max stuff can be heard in the Last Ride Of The Day, which will be named differently for the movie and the OST. A rollercoaster usually makes a ticking noise when speeding through the track – so immediately I thought about taking Jukka’s overhead, high-pitched, crystal clear cymbal/hihat/leaking drums and chop them into 1/16th notes, carefully fading out the end of each hit. Added a resonator to enhance the metallic tone – then put it through Corpus to add some “noise components”. Then added some multiband compression to tame out wild lower middle frequencies. That was probably one of the easiest things. Usually the process got out of hands when I just kept going further and further for hours, just playing around. It didn’t take too long to prepare “a path” inside your brain – you heard a raw track and immediately figured out what it could be turned into. After the first week I was literally swimming in files. There were thousands of them, everywhere. Folder after folder filled up. If I prepared a pitched loop, I’d prepare every semitone as well, so if the pitch was supposed to spread over two octaves, I made a separate sample for each key. Transposing a sample sounds worse than playing a specifically prepared sample for that particular key, in my opinion. To make things even more complicated, the pitching was seldom enough. Usually a blend of Ircam Trax in conjunction with some other esoteric plugins was implemented. It was an amusement park, truly.

I really loved putting toms and kickdrums (and taiko as well) through Corpus, turning them into huge bass synths with a percussive envelope. Arabesque is one of the tracks that utilised that technique. A booming, pulsating groove underneath the ethnic percussion… sweet. Delicious. If Corpus only were a reliable when it comes to tuning. Let’s just say a lot depends on its input. Tough transients make it bow and bend, I’ve noticed. When these sub-bass pitched components were mixed in with the original instrument, together they created something wonderful. I knew I was to walk the right track.

Emppu & Marco faced similar treatment, although the tools were somewhat different. I sometimes removed all noisy components (as in tonal versus noise) from the signal, leaving only a mass of sine waves – or rather, a shred part without the harsh edge… would it be called “fredding” then? The outcome of this process has thousands of “glassy” artifacts, which sometimes are delicious, sometimes not. I went a bit far with some guitar stuff, as I pitch-perfected each string separately, and not only that, sometimes I removed all pitch fluctuation from the low A and E strings to “keep the package together”. Of course, after reamping, it was no longer a guitar as such, instead, it became almost an ethnic instrument due to the strange flavor it got in the tuning process. Luckily the stringed instruments provided me with enough material for some of those really low brass-sounding stabs that echo in, for example, the teaser. Of course, those ROAAARR stabs are always doubled (or rather, quadrupled) with something else, as it’s all about texture. A bit like looking at a really good picture: if you see a beautiful portrait, you probably see the skin first, then you pay attention to skin glow, irregularities, maybe hair too, the makeup, clothes, lighting, posing, environment, dust in the air, the moustache on a woman… it’s not “a portrait” of a hairless naked transparent albino cave olm floating in space, it’s an interesting person in a realistic setting realised by professionals. The final work of art consists of thousands of details; layers.

Usually using just “a sample” creates that olm feeling. Layering two sounds makes just… a pair of olms. I’ll return to this a bit later.

Sometimes the two shredding masters of Nightwish created a groove that had a magnificent “suck” to it, their playing was literally in a pocket. Unfortunately – forgive me for saying this right after praising their playing – the riffs they played quite often employed notes not necessarily feasible for transposing, all the semitone/tritone jumps. They are incredibly effective for pounding the stuff through in one key, but I couldn’t use them as such, I needed to cheat a bit. During the listening/preproduction stage, I usually start forming a track inside my head, not necessarily knowing what I’m doing – it’s an almost subconsious process, where I grab a chorus chord progression and try to fit in another part of the song, which often was in a different key. It’s a process of “I could use this. And this. Maybe that too, and those”, picking up what I loved in a certain song – or songs – then glueing them all together by means of technology. And often all of the aforementioned tracks/stems were in a totally different key. Including the orchestra. And the ambience channels, too.

Also, for creating the riffing guitar/bass parts, I had to create straight riffing/shredding patterns out of the original parts, which included a lot of jumps. Which had to be taken away, still retaining the original groove. I just had to cut off the “wrong” or “unneeded” notes and replace them with surrounding chugs/notes from similar subpositions elsewhere. By just replacing a second 1/8th note of a second beat with something from a different beat destroyed the groove. Definitely not a good idea. So – I just had to listen to the tracks really carefully and find exactly the right beat, right note with which I could cover up the hole left in the original groove.

By now you start thinking “why the hell didn’t he just call in the guys and have them play it for him” – but it would’ve been against the concept. And timetables. When I started pre-production phase, they had different engagements to the album, tour preparing, vacations… there were many different things. And – my luxury – I had plenty of time to mangle the stuff beyond recognition. Why wouldn’t I do that if I’m allowed to? Projects such as Imaginaerum OST are a rarity. When I come across one, I use it for studying as well, as I’m constantly eager to learn new things.

After the holes were filled, I needed to create realistic transposing for the gtr/bass patterns. Also, as I really wasn’t too sure in which tempo/tempi the certain tracks were setting into, I needed to have the shred patterns disconnected from their original BPM. Oh crap. Enter Native Instruments’ Kontakt 5 – a brilliant, brilliant sampler plug-in, a piece of software that works as a stand-alone application or, which is how I use it, as a plug-in inside my choice of DAW (digital audio workstation), Logic. Their previous version, NI Kontakt 4 had some issues with transpositional artifacts, especially when using the more specialized versions of the sample playback engines, Tone Machine as well as Time Machines 1 and 2. Luckily, their version 5 fixed nearly all of the bugs, and their newest Time Machine Pro sounded realistic, even with signals containing a lot of distortion. After a few short tests I was convinced with the results, as the transposed sections blended in with the untransposed rather nicely. I did a few artificial transposed versions to extend the tuning ranges for more… well, dramatic sections. Drop C tuning was still a bit high at times… I was afraid I’d lose the coherence of the low end in Marco’s and Emppu’s playing, but with some help from my Symbolic Sound Kyma system, I was able to create a bunch of murderous, angry tones which kept their tuning really, really well. Kyma is a hardcore DSP scripting/processing/creating environment, virtually a tame black hole. You can easily lost days whilst noodling with it, just testing out a few algorithms. All the most memorable sounds in the 90’s and 00’s and 10’s are – almost without exception – treated with Kyma. With a reason. That… thing is like a superhero amongst humans. The quality of its output is always above all expectations (greetings to Carla Scaletti and Kurt Hebel), even though the user were an idiot. I know what I’m talking about.

After the additional transposes were finished, it was time to put together a virtual Emppu/Marco entity. EmMa? Marppu? Emco? Just dragging the right samples onto the right notes in Kontakt 5 and spreading the key groups gave me a reasonable assurance; yes, this works. I added a round-robin feature (which randomly selects a different, yet similar sample from a specified stack of samples, thus preventing a stupid machine-gun-like effect usually associated with badly prepared sample sets) and some volume control, filtering, even a slightly randomized multiple eq settings (only +-0.5 dB with narrow Q values)… every trick I knew – and it sounded even better. The finished EmMa (sorry, guys) allows a rather large tempo adjustment, +-30 BPM away from the original 157.0139, so I could use it in other OST cues as well. Brilliaaaaaant!

Making a virtual bassist from Peppepappa on Vimeo.

Note: similar approach was taken with Emppu’s guitars. Nobody was left aside. Kontakt 5 can be seen in the latter section of the video.

But, without the true passion of the original performance, it would be nothing. Again I must emphasize the fact that the tracks oozed with artistry and passion, yet they were executed with immaculate professionalism, no glitches whatsoever. It was a set of every sound designer’s wet dream; not just a bunch of tracks for raw material, but a bunch of tracks with a Meaning. They had had a lot of fun during the recording, I’m sure. You can hear it.

Whenever retuning was ever needed (a rarity, unless I was after some effects), my choice of weapons were Melodyne (which produced quirky end results at times, probably due to complex input signals), AutoTune (for extreme quirky effects), Reaktor (grain cloud stuff and eerie stuff) and Zynaptiq’s PitchMap, which thankfully came out just in time before the final production phase. The last one, PitchMap (PM) got used a lot, in some song structures there were about a dozen or so instances. PM allowed me to change pitches polyphonically in realtime, without preprocessing. I wish every DAW application had PM as a built-in tool, it’s that versatile.

Whenever retuning was ever needed (a rarity, unless I was after some effects), my choice of weapons were Melodyne (which produced quirky end results at times, probably due to complex input signals), AutoTune (for extreme quirky effects), Reaktor (grain cloud stuff and eerie stuff) and Zynaptiq’s PitchMap, which thankfully came out just in time before the final production phase. The last one, PitchMap (PM) got used a lot, in some song structures there were about a dozen or so instances. PM allowed me to change pitches polyphonically in realtime, without preprocessing. I wish every DAW application had PM as a built-in tool, it’s that versatile.

Another trick I used often was Melodyne’s polyphonic correction tool (when it worked). I sometimes bounced an orchestral riser (a crescendo) off the Protools projects and imported it into Melodyne and had it analyzed with the highest possible setting, then meticulously retuning the lower notes onto absolute notes separated by an octave (or two). Even though the original riser was dissonant, the retuning brought it back to normality, but I was able to control all the harmonics with the retuning process, sometimes removing the pitch fluctuations completely from certain frequencies, sometimes exaggerating it by 100% – as much as I could. The results are heard in the first reel of the movie, in the second open-air scene with the main characters. If you can hear a sound resembling a bomber plane screeching through the clouds at about 13 minutes and 44 seconds from the start, it’s an orchestra. Brass section. Note: as these are “work-in-progress” files, you’ll hear a lot of artifacts. The final files are in the Imaginaerum OST.

Another trick I used often was Melodyne’s polyphonic correction tool (when it worked). I sometimes bounced an orchestral riser (a crescendo) off the Protools projects and imported it into Melodyne and had it analyzed with the highest possible setting, then meticulously retuning the lower notes onto absolute notes separated by an octave (or two). Even though the original riser was dissonant, the retuning brought it back to normality, but I was able to control all the harmonics with the retuning process, sometimes removing the pitch fluctuations completely from certain frequencies, sometimes exaggerating it by 100% – as much as I could. The results are heard in the first reel of the movie, in the second open-air scene with the main characters. If you can hear a sound resembling a bomber plane screeching through the clouds at about 13 minutes and 44 seconds from the start, it’s an orchestra. Brass section. Note: as these are “work-in-progress” files, you’ll hear a lot of artifacts. The final files are in the Imaginaerum OST.

I often doubled the EmMa stuff with staccato or spiccato strings, or, celli and contrabass sections. I tried to use the original orchestral tracks as much as I could, but there were times when section and instrument leakage was so heavy I had to recreate it with samples. The leakage is unavoidable; there are dozens of players in the same room, all blasting off at the max volume, so they’re going to leak into each other’s microphones. I think they’d leak even though contact microphones were used (which grab the signal through a resonating solid material, not through air), the sheer volume of everybody playing forte fortissimo makes everything resonate; brass, wood, strings, cymbals. Everything. The leaking makes a part of the sound, it unifies the sound field, melts every single instrument into one big instrument: an orchestra. Without leaking it would sound like a badly done synth orchestration, sterile and embalmed. Dead. Leaking & dirt = good. Just as in real life: good sex is always a bit dirty. I think I’ve said that before…

After some heavy testing, I chose LASS (Audiobro’s Los Angeles Scoring Strings sample library) to accompany the shredding. Sometimes I emphasized the sound with some other sample sets, even with some staccato low end brasses as well, but about 70% of occasions, I managed with LASS alone – although with several layered sections, doing slightly different things.

Yep. Layers. There are a lot of them. If there’s a pad, it’s not just one pad or blast or choir or whatever, it’s a choice of three, four, don’t-know-how-many sounds each playing a bit different part. The more further away the notes of a certain part are, the quieter it is. Often thinner, too. Sometimes I layered a “resin” sample with a granular choir, to make it sound a bit string section-like. There was a lot of controller info, sometimes affecting a parametric EQ, sometimes the amount of granularity (i.e. more granularity creates a decomposed sound made of bits and pieces of the original signal)… and always the layers were tightly tied to certain frequency areas to keep the whole patch easily playable. Actually, now that I’m looking at the instrument sets I’ve done, I’m quite convinced that almost everything could be played live with some careful planning, but it would require a lot of work and a large sampler or a workstation. Maybe two or three.

Here’s a real-time demo á la Imaginaerum OST (just a noodling, improvisation):

As I said earlier, I’m more player than a geek. I’m very fond of instruments that are simple to create with, which is my “secret weapon”. One can have the most incredible sample library at hand, but without at least a decent usability it’s worthless. I seldom take sample libraries as is, usually I’ll spend at least a month or so creating my own set of instruments which I can handle easily, without extra thinking. In a creative are such as mine, it is imperative to know your tools and how to get everything out of them. You must concentrate on the creative side and raise above the technical issues. You must be able to think quickly, without a hinder. You must be a mad geek to tame all the power, but you also must be able to express your passion through playing. The tech is there to be conquered, it is a good worker but a lousy master.

I must admit I felt a bit embarrassed to treat Tuomas’s keyboard tracks in any way. He’s an excellent player and just being able to dissect his compositions felt a bit odd at first. If possible, I kept his keyboards in every cue as long as possible, but since the original performances were audio only (no editable midi data available, thus preventing me from using his playing with other sounds, other than recorded ones), I faced a dead end every now and then. For instance, if a cue needed a softer piano or fewer notes, it didn’t exist. It had to be recreated. To an extent, I could use Melodyne Editor. It took most of the piano parts without pain, but just as soon as there was some harmonic or phase movement, it ran into problems. Luckily the aforementioned PitchMap arrived in time. However, if I needed to create a midi file from Tuomas’s playing, it had to be done with Melodyne, which can output the notes contained in an audio file into a certain type of file that can be used in every DAW application. The moral? Screwdriver isn’t enough. A carpenter needs a saw and a hammer too. And quite a few other tools as well.

Sometimes even that, the whole toolbox, didn’t do the trick, and I had to play a lot of stuff in myself. I aimed for maintaining the original voicing and the choice of intervals and chord inversions whenever possible, but at times I had to create a section from scratch, or the movie needed something that couldn’t be found on the Protools projects. Needless to say I was overnervous when sending a such track to Tuomas and Stobe (Harju, the director of Imaginaerum, who also wrote most of the screenplay), because if there had been anything not worth a shit, they’d surely kicked my ass immediately, although politely. Think about Alan Rickman saying “how grand it must be to have the luxury of not fulfilling the expectations. Now go back to your pathetic chamber and concentrate like your life depended on it. Which it, of course, does.” To be honest, none of that ever happened, but I sure felt like a wand-waving apprentice at times. Turning gazelles into frogs, or, with some luck, into unicorns.

Of course, the processing didn’t end there. Sometimes I had to get rid of trombones leaking into everything else, sometimes – although it was a rarity – flutes were playing on top of a perfectly usable high violin/viola motive. Eventually I started questioning my sanity, and especially the methods I was using? Did I really have to do this and that. I spent literally dozens of hours with Sonicworx•Isolate, which allows one to “draw off” unwanted signals. By December, it was really painful. I found errors in my versions, things that didn’t fit in, or was just lame, repeating itself, or sub-quality in my opinion. Or did I just imagine everything? The project started to haunt me, and a short while I was really angry to let people hear something I wasn’t sure of. During the first two weeks in December I re-did a lot of stuff, partially due to the first finished cut of the movie, as there were a lot of off-beat picture changes which I had to take into account, make tempo changes, re-arrange etc. Slowly, the versions were reformed and it was as if a new backbone had been installed. Finally, the clicking into place started.

By December, it was really painful. I found errors in my versions, things that didn’t fit in, or was just lame, repeating itself, or sub-quality in my opinion. Or did I just imagine everything? The project started to haunt me, and a short while I was really angry to let people hear something I wasn’t sure of. During the first two weeks in December I re-did a lot of stuff, partially due to the first finished cut of the movie, as there were a lot of off-beat picture changes which I had to take into account, make tempo changes, re-arrange etc. Slowly, the versions were reformed and it was as if a new backbone had been installed. Finally, the clicking into place started.

I’ve used the term loosely here, “clicking”. But it describes perfectly the feel I was after. Puzzle pieces should just click, they shouldn’t be put into form with force. If force was used, the pieces would break and render unusable, creating just a mess. I felt the score needed a few lighter versions to counterweigh the angry and sinister side. Mermaids and CrowOwlDove happened that way – actually, even though COD is a shorter version than its original, it is one of my favorites, as the chorus/verse parts were mixed, and the song structure really builds into something else. It was a song virtually conceived by mixing up the pieces and rebuilding it blind. Or rather, deaf. I just looked at the previews, the sausages – or the continuous wire waveform – and cut the pieces without having my loudspeakers on, just trusting my instinct. The end result was surprising. Of course I had to hone out a few rough ends, but it did sound rather good. I fixed a few fighting notes from the lead vocal and that was it.

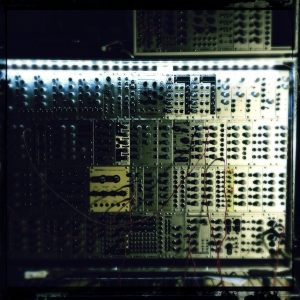

If I should explain why I chose the parts I chose, I think my most overused answer would be “I felt that one would be a nice one”. I made those choices very, very quickly during the first few listening rounds, just ran blind, trusting my gut feeling. There were bass hits, single drums, percussion rolls, orchestra blasts/crescendi/whatnot – and sometimes I chose just noise, noise from the orchestra’s ambient channels.  Sometimes a chose a leak, say, trombone leaking to doublebass channel, or vice versa. I wasn’t after the most beautiful single note or phrase, I was constantly looking for dirt and interesting, fiddly parts that would benefit a lot from corrections and/or editing. A lot of ambience stretching, denoising and retuning was done to create the surreal pad instruments often decorating the simpler scenes. Of course, there are a lot of commercial libraries and software instruments involved, as well as my trusty hardware gear – especially my modular synth, which processed a lot of the tracks and even got to be used as an ambient piano in the beginning scene! There are a lot of lower midrange growls from my trusty old Oberheim Xpander. Some guitar parts were doubled with a Dave Smith Mopho Keyboard, a tiny monophonic analog synth, as its sound structure is just perfect for my use, and I can get it sound like an angry banshee on a charcoal grill.

Sometimes a chose a leak, say, trombone leaking to doublebass channel, or vice versa. I wasn’t after the most beautiful single note or phrase, I was constantly looking for dirt and interesting, fiddly parts that would benefit a lot from corrections and/or editing. A lot of ambience stretching, denoising and retuning was done to create the surreal pad instruments often decorating the simpler scenes. Of course, there are a lot of commercial libraries and software instruments involved, as well as my trusty hardware gear – especially my modular synth, which processed a lot of the tracks and even got to be used as an ambient piano in the beginning scene! There are a lot of lower midrange growls from my trusty old Oberheim Xpander. Some guitar parts were doubled with a Dave Smith Mopho Keyboard, a tiny monophonic analog synth, as its sound structure is just perfect for my use, and I can get it sound like an angry banshee on a charcoal grill.

More about bad samples: Just using a good snippet would be comparable to taking a picture of Mona Lisa’s shoulder and glueing it into your canvas. Then repeating that, until you’ve got a Mona Lisa Polaroid Puzzle. It could be interesting, but the outcome would still be merely a bad copy of an original masterpiece. My philosophy was to sketch Mona Lisa’s shoulder onto white paper with a pencil, then take my polaroid and mangle the polaroid beyond recognition, creating a “multi-technique collage” that would possibly have a life of its own, disconnected from its origins, yet nodding towards them with respect. I just wish I could’ve used those funny and dirty sounding eerie pads even more, but the movie had almost an action vibe to it, especially closer to the end.

And that vibe needed a healthy dose of percussive instruments. Some of it is from Tonehammer, which later on became 8dio and Soundiron, some of it is my own library I’ve recorded throughout the years, as I began doing this when I was in high school, some of the samples I use even today were originally sampled into an Ensoniq Mirage, back in 1986. Oh, the agony of not having enough memory! Things are quite different today. Sometimes I needed to employ three computers, one took care of the percussion, another took the strings and main machine did the rest. They were connected by means of Vienna Ensemble Pro 5, which allows one to connect multiple computers with an ethernet cable, carrying midi and audio signals. During December, I installed multiple SSD drives into my system, removing the “your computer is too slow” message almost completely. I regret I didn’t do that earlier. Not every cue required three computers, though, especially after the SSDs entered the house. About 95% of final mixing/editing time, one Mac Pro was enough. It was only the most crowded string and percussion arrangements that needed a few extra hands.

I personally happen to like lower frequencies a lot. With some careful programming and arranging one can cause the toughest cold turkeys, making each hair stand like they were dropping off suicidally. In the autumn 2011 I began experimenting with piano and harp, as well as brass instruments, which I noticed benefit from pitching down their tuning. I collected a lot of lower midrange and bass instruments from my libraries and Nightwish Protools sessions, and created some hybrid instruments based on the lowered samples. The results? Let’s just say the tripods from The War Of The Worlds remake were their little brothers. Also, it was a respecting nod to the other epic direction: Inception. It was almost obligatory to incorporate keyboards into the sound, both Tuomas and myself being keyboardists. I also happened to have a background of playing pipe organs (I probably had the best teacher in the world – whom I didn’t appreciate at that time, unfortunately: Kalevi Kiviniemi), so I put in some of the lower, richer reed stops that were recorded in Lahti in a church back in the early 90’s. I’d definitely like to re-do that session, by the way. That and a grand piano. And a harp. And EmMa. And… a Novachord? Actually, not a real one (as it’s beyond most people’s budget).

Improvised á la Imaginaerum OST:

(By the way, look for Kalevi Kiviniemi’s version of Gabriel Pierné’s Prélude, Op. 29, No.1 from iTunes and let it play – it grows slowly. By 1’35” it turns into a gothic masterpiece. THAT is how you play organs, note also the grand, lush ambience of a gothic church it was recorded in. The G chord ending that one is something unreal. I’ve been practising a lot lately, so I might match him as early as 2040. Maybe sooner, with some unexpected luck.)

With some songs I regretted the order in which they had to be incorporated into the movie. For instance, one of the “underused” tracks was Song Of Myself, an epic that should’ve had more room, but alas, the script was changed and most of it had to be taken away. The most beautiful part of it is still there, luckily. Without giving out any hints of the plot or the script, I’ll say it underlines one of the most beautiful and wistful moments of the movie, with a firm yet tender voice.

I used a lot of choir and vocal takes from Imaginaerum The Album – but left most of them alone, choirs weren’t processed or turned into dinosaurs wailing at the peak of their climaxes, nothing like that. I felt it was important to preserve yet another element from “classic” Nightwish – although I created a monster monk chanting crowd based on Marco’s incredible voice. Anette’s lead vocals appear here and there, and in a few occasions one lead vocal and its doubles were turned into a choir of 30+ vocalists. Her voice, however, was so clear and pure, that it felt a bit awkward to mutilate it in any way. A bit like employing some bradpitt and putting a monster mask on him for the whole movie – what’s the point?

And no. Brad’s not in this film.

If you’ve really read this far, I’m nothing short of amazed. WIth all these references to technical issues, applications and plugins, text becomes easily stodgy and onerous. I’m sure I’ll write a few more lines in the future – maybe dissecting a few scenes sonically, but it’s a totally different story then.

Cheers, enjoy the ride!